Welcome to ƛuukʷatquuʔis (Wolf Ritual Beach), this is the site where c̓išaaʔatḥ held their ƛuukʷaana (wolf ritual ceremony). Our ƛuukʷanna was a deeply sacred ceremony rarely spoken of and was organized by a person of high rank, usually it was a ḥawił (head chief) who held this right. These were on the most important ceremonies held by c̓išʔaaʔatḥ and the other nuučaan̓ut (Nuu-chah-nulth) Nations up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island.

The ƛuukʷaana was a deeply spiritual practice that helped prepare c̓išaaʔatḥ for thier roles and responsibilities as a community member along with the way tutuupata (ceremonial rights) were communicated and shared to c̓išaaʔatḥ members.

A ƛuukʷanna was held over fourteen days however, some would last up to twenty-eight running with a full cycle of the moon. Guests to these ceremonies were well taken care of over the period the ceremony took place.

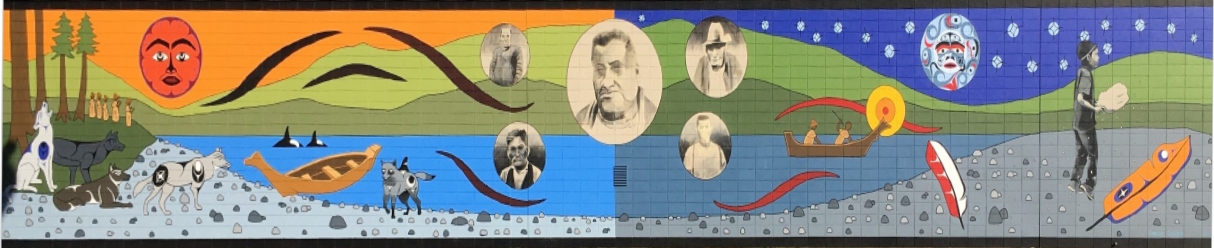

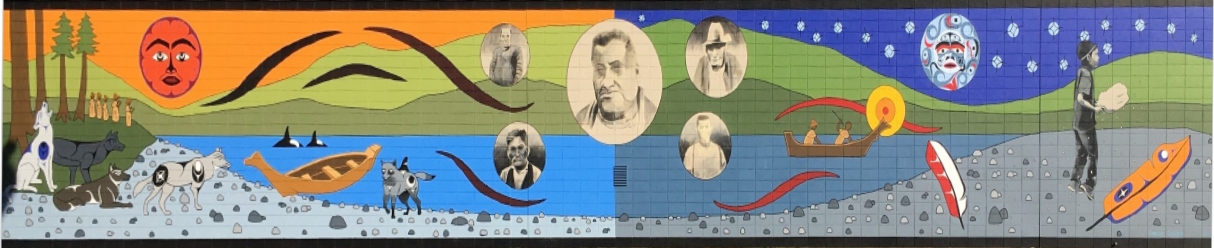

Rotary Mural Description

Transformation

The mural has an underlying element of “transformation” throughout the design; The orca transforming into a wolf on the beach, the day into night; the past to present, the humans to wolves.

hišukʔiš c̓awaak (Everything Is One)

There are several elements which symbolize c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) link between the past and the present AND morning and night. The left side of the mural represents the day and the past. The right side of the mural represents the night and the present. The round painted drums with the ḥaw̓iiḥ (Chiefs), represent the spiritual transformational heartbeat of the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) songs owned by them for every occasion.

The wavy lines represent the connection to the spirit world; the link between c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) ancestors of the past, to the people of present day.

The c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) boy (Bryan Watts) holding the nač’a (eagle tail feathers) symbolizes how our Tseshaht teachings and culture, past down by our ancestors, is still alive and thriving today.

Feathers

The 2 eagle feathers on the right are included to show their importance and sharing significance in c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) culture.

Canoe (c ̓apac)

The canoe on the beach, a design unique to c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) people, symbolizes the Tseshaht connection we have between all life; hišukʔiš ca̓ waak (Everything is one).

Torchlight Fishing (hišaak)

The canoe on the right with the two c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) fishermen and a glowing light on the bow, shows one of many historic Tseshaht fishing methods called hišaak, torchlight fishing that was done in this very harbour. The tools and techniques may be different

nowadays but c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) way of life still exists.

Sun and Moon (hupał for both)

The people standing on the hill, facing the morning Sun, are asking and thanking n̓aas (creator) for protection throughout the day. In the evening, the creator is given thanks for the day. The Moon, which represents valuable harvest times, changes of seasons and spiritual activities, is shown in the night sky.

Significance of 5

You will notice that the number 5 is seen throughout the drawing; the 5 people standing on the hill, the 5 wolves on the beach, and the 5 drums in the centre. The number 5 signifies the amalgamated tribes which make up c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) as described in detail below.

ƛukʷatkʷuuʔis, (wolf ritual beach)

The overall scene shows the harbour and c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) lifeblood, the c̓uumaʕas (Somass) River mouth, which is drawn from the deep history of where Tseshaht sacred winter village site, ƛukʷatkʷuuʔis, (wolf ritual beach) once stood.

We are the c̓išaaʔatḥ

We are the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation), a First Nation Tribe of the nuučaan̓ał (Nuu-chah-nulth) Peoples. c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) has over 1300 registered members whose ḥaḥuułi (territory) includes from the Somass watershed including the entire Alberni Valley, the western portions of both Horne Lake and Cameron Lake, the Alberni Inlet surrounding lands and watersheds to the Broken Group Islands of central Barkley Sound, and out the the Pacific hiłc̓aatu (ocean). Tseshaht possesses Aboriginal Right within the ḥaḥuułi (territory) owned by our tayii ḥaw̓ił, including Aboriginal Title.

c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) have lived here on the west coast of Vancouver Island for over suč̓a (five) thousand years. We lived in eco-spirit harmony with nature and both thrived with nism̓a (land) and sea resources plentiful as our system was in balance. This was mainly a result of harmony laws passed onto the first c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) man and woman after they were created at c̓išaa (Benson Island), our home village on Benson Island.

This core c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) belief of the principle of balance is called hišukʔiš c̓awaak in our language, it means “everything is one” and it’s the understanding that ‘everything is connected’. Our hišukʔiš c̓awaak core teachings ensured that all łim̓aqsti (spirits) thrived in our homelands.

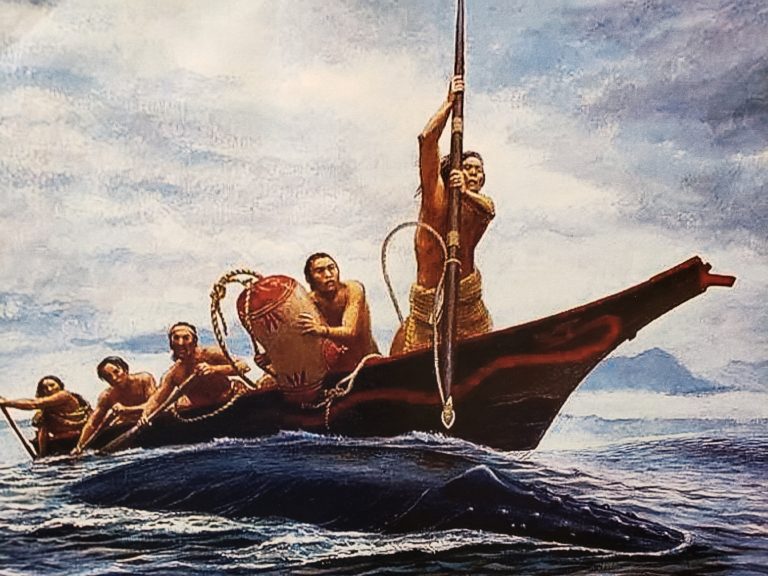

Our name is inseparable from these teachings. c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) means ‘people from a rancid, smelly place’ because of the plentiful bodies of ʔiiḥtuup (whales) c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) harvested that made the village rancid and smelly. This is a sign of honourable wealth gained from upholding this core teaching.

c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) hahuułi has greatly expanded over the past centuries through marriage and alliances, warfare, and the incorporation of affiliated groups or Tribes estimated to be between the years 1780 and 1815.

Eventually c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) nism̓a (lands) included the ḥaaḥaaḥuułi (territories) of the assimilated groups, in the Broken Group Islands, central Barkley Sound, much of the Alberni Inlet, and the Alberni Valley.

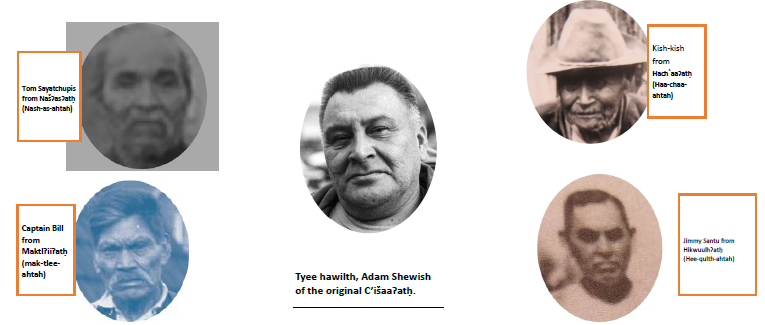

The c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) absorbed the maktlɁiiɁatḥ, našɁasɁatḥ, hach`aaɁatḥ, and hikwuulhɁatḥ who brought their nism̓a (lands) and č̓aʔak (waters) with them, as well as the once independent ḥaḥuułi (territories) of of the original c̓išaaʔatḥ.

This is why the mural has ʔiiḥ (large), nuutximł (round) traditional t̓icky̓ak (drum) like images of members of those nations above such as; Captain Bill (lower left image) from maktlɁiiɁatḥ, Tom Sayachapis (top left image) from našɁasɁatḥ, kishkish (top right image) from hach`aaɁatḥ, Jimmy Santu (lower right image) from hikwuulhɁatḥ and tyee ḥaw̓ił (King) Adam Shewish (center image) of the original c̓išaaʔatḥ.

Sharing of wealth as was the tupaati law

The ownership and use of these nism̓a (lands), and practically everything of value in the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) ḥaḥuułi , were governed by tutuupata (the plural of tupaati), a complex set of hereditary privileges or prerogatives. Tutuupata instructed the ways in which both economic resources, such as c̓aʔak (rivers), saamin (fish) trap sites, and plant gathering sites, as well as intellectual property resources, like ʕeʕimtii (names), ceremonial nuuknuuk (songs), huyaał (dances), and ʔiinaxma (regalia) should be owned and utilized. Tutuupata determined rank in c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) society and were inherited within a family. Tupaati laws don’t merely give a c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht person) wealth; you are entitled to give a ceremony which is yours, and you must validate tupaati by distribution of gifts. Historically, much of the tutuupata redistribution was done at the winter village of ƛuukʷatquuʔis (Wolf Ritual Beach).

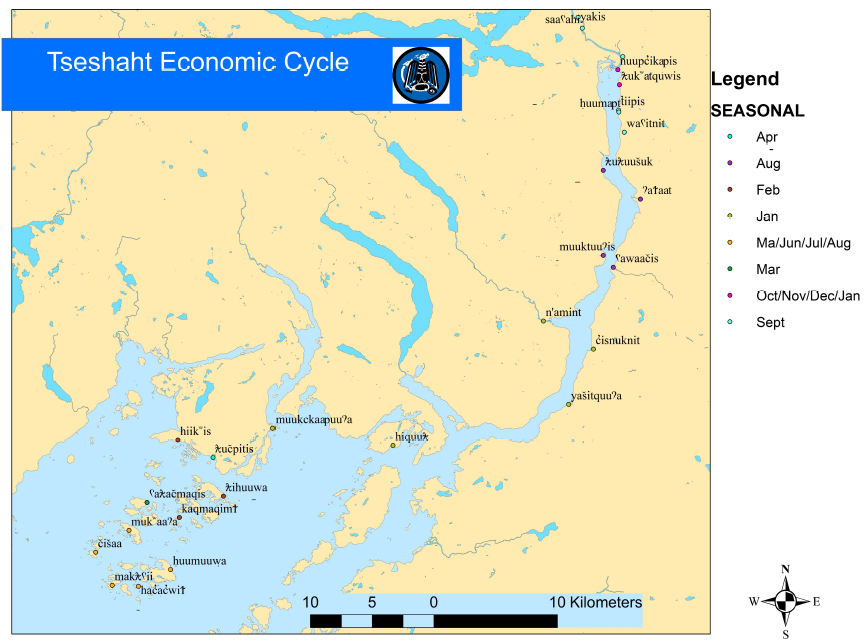

c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) Seasonal Round (Economic Cycle)

Our historic and traditional c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) economy was mostly determined by tupaati – the designated ownership and use of ḥaḥuułi (territory) resources. Tseshaht tupaati included both outside and inside nism̓a (land) and sea resources throughout the ḥaḥuułi (territory) and its watersheds.

After amalgamation of the various groups had occurred, the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) had a much larger ḥaḥuułi (territory) with a broader resource base. This meant that in late c̓ułičḥ (winter) and early ƛ̓uʕiičḥ (spring) the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) travelled to their hitaas “outside” ƛ̓up̓iičḥ (summer) tupaati to utilize the resources of these traditional sites and procurement areas in Barkley Sound. These included all nism̓a (lands), hiłc̓aatu (ocean), c̓aʔak (rivers), ʕaʕuk (lakes) and it’s resources such as sea mammals, p̓uuʔi (halibut), rock-fish and saamin (salmon). As the seasons changed, the resources changed, and the

c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation) would move back to their inside winter tupaati, following the salmon up the Alberni Inlet to the c̓uumaʕas (Somass) c̓aʔak c̓ułičḥ (River) to celebrate the c̓ułičḥ (winter) sharing of wealth.